Crafting Metaphors

The Potent Poetry of Paper Mache

When I was a little girl, I loved to make things. From turning an old cardboard box into an epic boutique for my Barbies to creating jewel-encrusted ornaments out of Styrofoam balls and yarn for Christmas, I’ve always been hard-wired to transform things, to fix what’s not working—or at least try. Tin foil can make a fabulous full-length fashion mirror, and a broken rhinestone necklace can make a dramatic holiday statement.

One craft I remember well was paper mache, a messy sculptural process that involves dipping scraps of torn newsprint in a murky mixture of water and flour that hardens when it dries. I made a circus elephant I painted purple and an odd, organically shaped globe that was supposed to be a hanging lamp.

Last Sunday, paper mache came up in a WhatsApp conversation with my dear friend Sue Ferguson, who lives in Denver, Colorado. We typically talk on Sundays, and we call it our “church” – checking in to listen with care, witness with compassion, and laugh with abandon at life’s most vexing absurdities and conundrums.

Sue is as much a spiritual shaman as a soul sister. We met in a virtual grief writing group during COVID that was orchestrated by another special seraph, Linda Joy Myers, author, memoir maven, and therapeutic light.

As we both carry the complicated and unimaginable losses of our first-born sons, Sue and I are members of a vile club that no one wants to join. Like my Elliot, her son Keith left life too tragically—and too soon. The associated seismic grief jolts continue to derail us five years later.

But the grace is we are not alone.

We gratefully opine that the universe conspired to connect us—adding sweetness to our sour stew, and last Sunday, the subject of our “homily” was choices—personal and professional, minor and monumental—how they can elevate, annihilate, and elucidate.

I confessed I often dive headfirst into new situations or opportunities that intrigue me. I’m all in with the eager vigor that any challenges or hiccups will be reparable, adjustable, or fixable. Making it OK—or at least better—is my M.O. Ah, but as I am learning in therapy school, that approach can be as unhealthy as it is pure fantasy.

“But not for nothing,” a grandiose former boss used to say. The universe also is teaching me that I cannot fix every chaotic situation I land in, nor is it my job. Most are not even mine to manage. Why is this such a difficult lesson? Well, mainly because it is embedded so deeply in my mitochondria that it’s virtually imperceptible—an automatic trauma response that seems to generate like A.I. to deliver the most constraining and chaotic arrangements to my orbit, particularly in work and love.

These gnarly situationships are so unconsciously familiar that they fool me into thinking I’m safe for a hot minute. If I can figure out how to pretzel myself into the mayhem du jour, I’ll be OK. In the words of Dr. Phil, “How is that workin’ for you, Elaine?” Well, not so great. But awareness is the first step, right?

I’ve noticed I’m not as adept at minimizing or internalizing dysfunction as I used to be—particularly since Elliot died. Maybe that’s another glimmer of grace in this gully of grief. As they say, recovery is not linear. And I am not the same person.

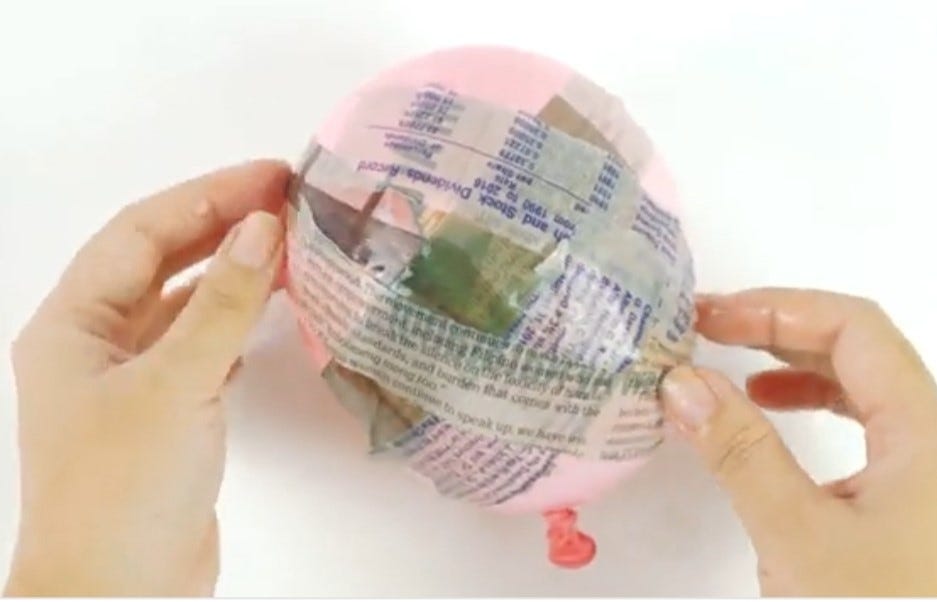

In this context, my insightful Sue brilliantly observed, “Reminds me of paper mache.” (Oh, how I love it when we run with an idea like this) “Layer upon haphazard layer, they construct a rigid outer shell of paper mache on a brittle skeleton or an inflated balloon,” she continues.

Overinflated with hot air . . . I add with a grin

Mindlessly applying torn strips of yesterday’s news with heaps of that opaque goo has its appeal, but the empty fragility inside remains. Yes, the layers obscure the stressed balloon—but the strength of the exterior shell is deceptive.

Oh, this is such good therapy.

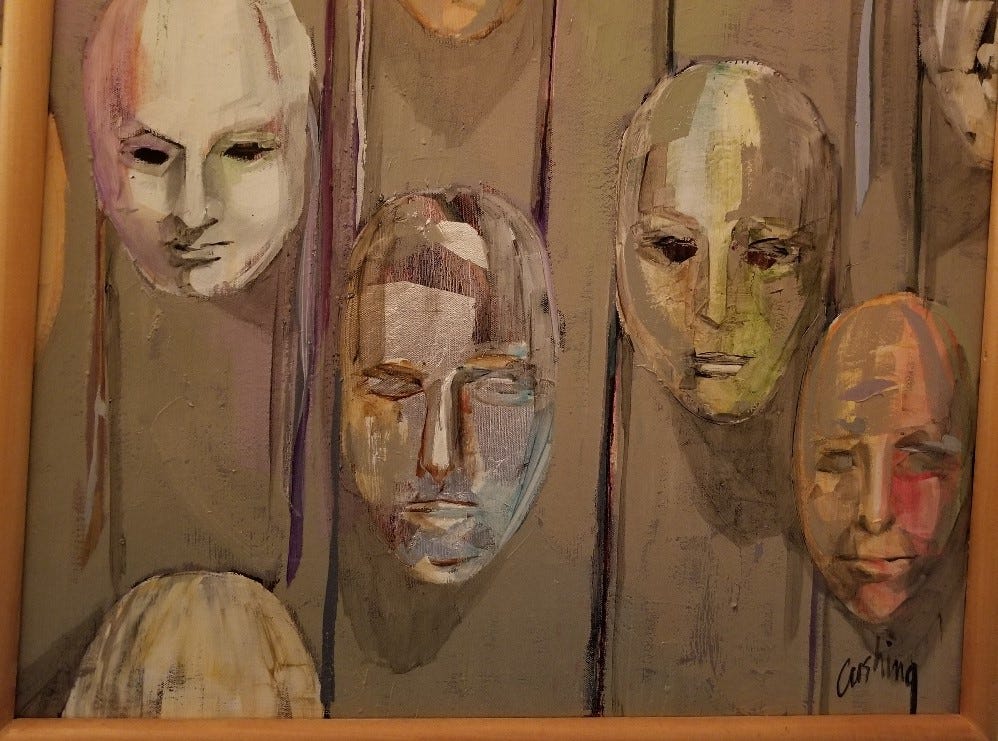

And then there’s the human form: that’s all about the mask, isn’t it? The artfully crafted and impervious façade. Thin yet solid enough to contain and prevent any real human connection or empathy. The quintessential paper-machester (another one of my made-up terms) is rarely accountable for their actions, nor do they acknowledge the impact of their behavior on others.

Protecting inner vacuousness trumps all.

And interestingly, it’s an age-old process. The French term papier-mâché means “chewed paper,” and historians confirm its use for helmets and snuff boxes in 200 BC China. Ancient Egyptians used a form of paper mache called cartonnage to make death masks in the First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BC) by layering cloth or papyrus with an adhesive mixture before painting.

For me, it’s time to bypass the metaphorical paper-machesters from the get-go. That’s my inside job. No more ferreting out the morsels of humanity and connection that are as conditional as they are fugacious.

How grateful I am for my precious, authentic, and nurturing relationships with the dear friends in my life—my cherished angels like Sue. Honestly, I’m not sure where I’d be without them.

The question is—what will I make next?

Recipe: Paper Mache

Ingredients: flour, water, spoon, bowl, salt (optional), and a pinch of spice

1. Mix 1 part flour, 2 parts water

2. Stir until lumps are gone and mix is thin

3. Add more flour or water if mix is too think

4. Add a couple of tablespoons of salt if you live in a humid climate where mold might grow

5. Add a pinch of cinnamon for fragrance

4. Store in refrigerator to use as needed

I remember you and paper mache. My gosh you were a magnificent creator; transformer; paper and glue into sculpture. As we grew older, your skill in this art form grew, matured, deepened. I was and am in awe of your process.

How you process grief, which is profoundly central (yes, I think it can be “ profoundly central”) in your experience and living, is an authentic and true expression of WHO YOU ARE.

Thank your open vulnerability, grace, and sharing of all of it.

Love nan (with gratitude to Susan and your grief community.)