Embracing the Ever-Present Past

On Christmas Day, so many memories conjure the presence of everything past. The sediment from impossible grief continues to sink out of the ordinary air, obscuring all and clarifying nothing.

But this year, I found a glimmer of a memory I may have never had. Perhaps, the sweet sting of hiraeth, a sense of nostalgia for a home that never was.

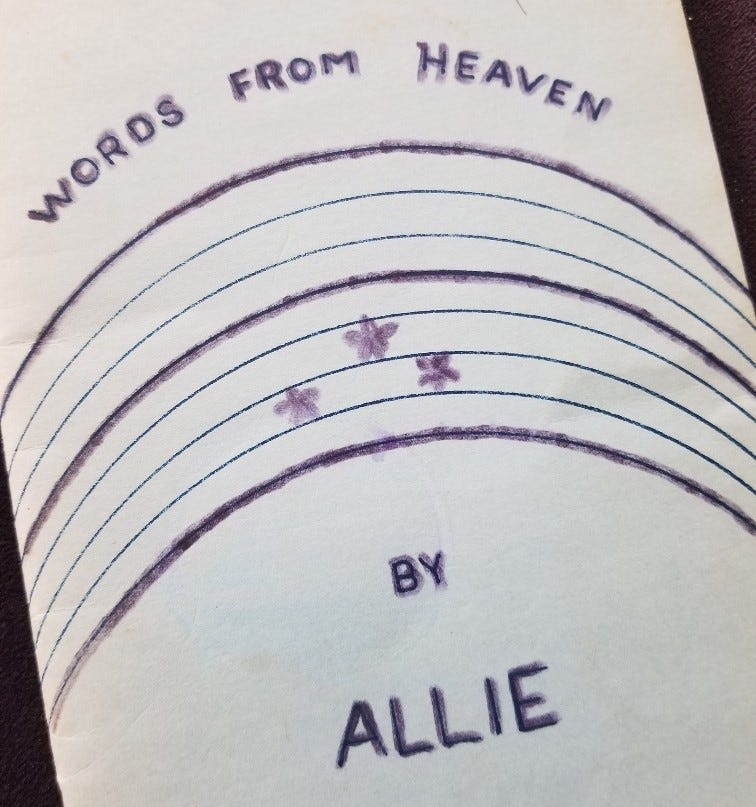

I pulled a tattered baby-blue booklet out of the old banker’s box. Titled “Words from Heaven by Allie,” the lovingly read book contained delicate, hopeful poems printed in the original Courier type. I had been looking for some holiday ribbon to finish wrapping a gift for my precious chosen grand-nephew, Henry, the first grandchild of lifelong friends. I did not remember the book, but there it was — hiding under a collection of would-be craft supplies . . . old Christmas cards, broken costume jewelry, my mother’s lingering containers of purple glitter, and a few gently folded pieces of lavender tissue paper.

Allie was a relative, technically speaking. Though I don’t recall ever meeting her in person, my Aunt Virginia, my father’s older sister and my only aunt, spoke often with overflowing fondness. There were several faded photos of her with people I did not recognize in a crumpled brown envelope.

To say my family of origin lacked emotional connective tissue would be an understatement. My essentially silent father, Everett, a stoic, brilliant aerospace engineer who worked in a top-secret test lab for 45 years, could do long division in his head. He was married to my mother, Ann, a grandiosely talented, yet elegantly insecure artist and teacher. Opposites attract, and sometimes, they enmesh.

There weren’t regular conversations in my house — more like alternating monologues and pronouncements. My mom’s favorite was opining about the philistine art world’s inability to discern good work. And when my dad spoke, it usually was about how artists can’t get along in the world because they are so ditsy. My mom would just laugh it off or roll her eyes as she lit another cigarette. That was their schtick.

“An artist can’t even add two plus two,” my father would quip. He was joking, but the message always landed. She would banter back, “Oh poo, Daddy, arithmetic does not mix well with art.”

But the Crown Royal did. The reality was that she took care of him and hid his secrets for decades — including his epilepsy, a form that presented primarily as complex partial or petit mal seizures. Out of nowhere, he would freeze, grimace, grunt, stare, and stroke the table or his leg with urgent repetition, but my mother would seemingly ignore the disturbing episodes, pretending they were not happening or changing the subject to deflect. Sometimes, he’d knock everything off the table and begin to drool, but there was never any acknowledgment from my mother.

When you are a child, you don’t think to yourself, wow, that is weird. You take what’s happening at face value. It still scares the living daylights out of you, and you end up developing a freeze, fawn, or flight reaction as an adult. It was one of many family traumas that would remain unexcavated — probably connected to deeply hidden shame and fear. What our family lacked in emotional connective tissue it made up for in unhealed wounds.

We discussed nothing of real consequence, ever — including my sister’s near-fatal struggle with anorexia nervosa; my only cousin Scott’s battle with alcoholism, which killed him at age 54, and the illnesses my mother’s mother succumbed to during her short time living with us when I was in seventh grade.

“Just pretend everything is OK, and have another brownie” was pretty much the modus operandi.

Not until I was almost 60 and digging into our family backstory for a memoir did Aunt Virginia reveal the most deeply obscured limbs of our brittle family tree. Allie, who hailed from a family farm in Vernon County, Missouri, was a critical branch. One afternoon we were having tea in Virginia’s assisted-living apartment a couple of years before her death during the COVID pandemic at 97. She paused and said abruptly,

“There is something I need to tell you.” She took a breath and confessed, “Your father had a horrible secret, and I think it’s time you knew.”

My heart stopped. I had no idea what she was going to say.

“He shot and killed a man, Billie Hoye, Allie’s first husband and your grandfather’s best friend, while they were duck hunting on a pond outside Omaha,” she said carefully. “It was a tragic accident, but no one ever knew exactly how it happened.”

I was dumbfounded and could hardly catch my breath. I had so many questions.

“Your dad was just 19 years old in 1944, but he took that secret to his grave. We swore never to speak of it again, but one thing I will tell you is that Allie did everything she could to comfort him. She was so kind,” Virginia added. Later, I found versions of the story on several genealogical sites online, so it was a known secret.

Virginia said there was more to tell. In 1951, Everett Sr. moved his family to Dallas, Texas to work for an envelope-manufacturing company. Soon after, Ruth, my grandmother and his wife, died from complications after gallbladder surgery, and soon after that, Everett Sr. traveled across the country to find Allie, Billie’s widow.

He proposed to her, and they married. She had been working in Wisconsin, but they moved to Palo Alto, California — I suspect to be closer to Allie’s family. My parents stayed in Dallas. The rest is history as they say. My father went to work for LTV, the defense contractor. He had met my mother at her first art exhibition in Dallas at The Black Tulip Gallery in the mid-fifties, and they married in 1958. To thicken that plot, I discovered in my serendipitous research that he was not only an art patron but also a silent partner in The Black Tulip, which was owned by notorious art smuggler Everett Rassiga. He hadn’t ever mentioned that one, either. But that’s another story.

I still feel overwhelmed by the troubling revelation that’s both unfathomable and in an odd way, understandable — as it explains some of the confusion and detachment I knew as a child. I was shocked and speechless when I heard this story. Living with this ubiquitous trauma must have been devastating for my hypervigilant father. I could not imagine the pain of holding such truth inside for seven decades. Unbearable.

Growing up, I remember hearing Allie’s name occasionally, but I never knew why. Like someone on television or one of my mother’s art students. Her relationship to us was not explained. Just “Allie in and Bill in California.” Bill was Allie’s third husband. They married after Everett Sr., died in 1960, the year before I was born. Gets complicated. Makes me think of everything, everywhere, all at once.

Over the years, Virginia visited Allie and her family frequently. She enjoyed their kinship and they hers. I believe Scott traveled with her in the years before his untimely passing. Though it was a bittersweet association, I suspect, with joy and grace — but with light and shadow.

I remember telling Elliot the story about a year before he died. He observed, “Well, no wonder Papa worked in defense. He knew how to keep life and death secrets.”

And I can’t help but ponder the cosmic connection between Billie and Elliot — both leaving this earth far too soon in violent, heartbreaking circumstances that still pose more questions than answers. An ancestral line of trauma, I suppose. I feel a chill when I think of Elliot’s fascination with vintage aircraft, like the Fokker Triplane, built in the 1920s during Billie’s lifetime. His first-grade teacher Ms. Rath marveled at his sophisticated vocabulary and knowledge of airplanes, positing, “How could he possibly know the word fuselage?” Indeed, it was one of his favorites.

Upon finding Allie’s faded musings on Christmas, I felt an undeniable connection, so I sent a message to Paula in Mountainview, California, my bridge to Allie, Billie, and their beautiful extended family. We found each other on Facebook several years ago, and I value our virtual friendship immeasurably. We exchange photos and news updates. Paula is such a gentle, and remarkably generous soul— assuring me we will always be family.

“Merry Christmas, Paula,” I wrote her. “I found a book by Allie called ‘Words from Heaven.’ It must have been in Virginia’s files. I thought of you today and will send it.”

“Hello Elaine,” she responded. “Christmas greetings! We have many copies of Allie’s poem book and other writings . . . Hope you’re managing the holiday well. Grief is hard. It’s amazing I read your message. At breakfast today Allie, Billie, and Rook were mentioned. My daughter and I teared up.”

I learned that “Rook” was my dad’s nickname when he was young.

She continued, ”The context was how Allie moved on in grief. And yesterday, we went to the Palo Alto cemetery, as my dad passed in July. Allie and Mr. Gantz were remembered in conversation as we drove by the street they lived on. We chatted about your mom’s painting and Alicia’s desire to hang it on the wall when her kids get just a few years older . . . Our family connection lives on. Hugs to you. Wishing for peace this next year in a world filled with turmoil.” — Paula

Such miraculous and mysterious ways of the universe. We are connected in so many ways I would never suspect and will never fully understand. But Allie did.

I think I would have liked her.

“Memory Lane” by Allie Ford Hoye Gantz Bartheld

Buried down deep

In the depths of my heart

Is a beautiful Memory Lane

Where I can wander

When day is done.

Where there is no sorrow or pain.

I hunt again for buttercups

And lie beneath the tree,

And watch the soft clouds overhead,

Go skipping across the sky.

These memories so dear to me

will never, never die.