I think resilience is overrated.

Our culture is obsessed with overcoming every adversity with fanfare — the hero’s journey that neatly deposits us on the other side of our valiant attempts to conquer the unthinkable. But some journeys don’t have heroes. They are about carrying what cannot be fixed — as grief expert Megan Devine accurately expresses. The expectation of resilience foists the weight of a power-through transformation on those of us who may consider putting one foot in front of the other a major accomplishment.

Resilience is a private road, deeply personal and candidly, its POV is often more about the beholder than the griever. I contend that resilience is best measured in moments, even micro-moments or mini-wins — not in a triumphant arrival at a pre-determined destination.

I admit it. Grief is uncomfortable – excruciatingly so for everyone in its orbit.

But as the brilliant Anne Lamott confirms, the most profound form of human connection shows up as compassionate presence — holding sacred space for someone when they are feeling like sh*t. There is no fixing required. No cajoling, sugarcoating, assuaging, minimizing, comparing, or deflecting. Even in silence, sharing discomfort helps us edge closer to the vulnerability that forges the most durable and meaningful relationships. It’s those times when we simply say, “You are OK. You are safe. You are loved. And this is frickin’ horrible.” These are the moments of radical humanity.

The more I force myself to feel better, the deeper my wounds become. There is no such thing as “healing on demand” — especially when a mother has lost her child. We are not rubber bands that snap back into place after we’ve been stretched too far.

There’s no going back — only morphing forward.

We’re more like a winding river of sorrow spilling into a crystal blue lake or a tumultuous sea. If we let the grief current carry us downstream, there is a certain inevitability it will dissolve into the larger pool of time and space. David Kessler, another grief guru says, “You must feel to heal,” and that means moving toward the shadows to fully integrate both the despair and the joy into our fragile souls. Integration does not mean “getting over it.” That is not going to happen.

Grief is the most mysterious and poignant form of human love — loving those passed into the present.

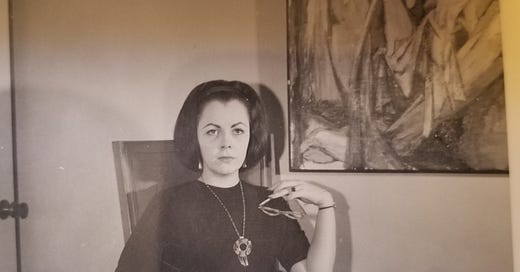

I guess that’s why Mother’s Day is never easy — shining a harsh, surgical light on the darkness I have harbored in my heart every single day since August 5, 2018. There’s also the added layer of my mother’s devastating illness and death 12 years ago. These griefs fuse and conflate with a constellation of others in my vast grief galaxy. Yet Ian, Elliot’s younger brother, and I still convene our micro-family each year to honor this complicated “Hallmark-manufactured” holiday (thusly termed by both my sardonic sons).

Yes, it’s messy, but the surprises do have a way of showing up.

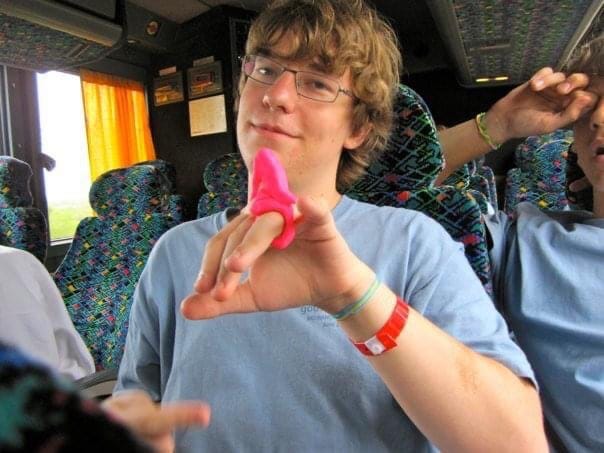

My pal Debbie showed up for me in such an unexpected and dazzling way this year. As I sat on my couch nursing a case of Mother’s Day food poisoning, she called out of the blue to tell me about a cache of photographs of Elliot she had recently found. She asked if she could forward them.

Heck, yeah, I said. One of my favorite things, I thought.

With each new image flashing on my phone, it was almost as if Elliot was greeting me in real-time. His beaming smiles and silly adolescent antics with his First Presbyterian Church squad filled my eyes with bittersweet tears. Seeing these photos for the first time — especially on this dense day — filled me with immeasurable delight.

This is the kind of micro-moment I am talking about — and a particularly potent one at that. Indeed, I felt it. Elliot was winking at me. This sign was unconventional but convincing, like Elliot, and the source was no shock, either. He adored Debbie, a sassy single mother of two teens in the youth group. He always enjoyed jousting with her rapier wit during our summer adventures at Mo Ranch in the Texas Hill Country.

How grateful I am for those times and precious memories.

Startling synchronicities like these — even when they might feel awkward, uncomfortable, or seemingly random — bring a rare order to the precarious chaos of grief. And I suspect that makes compassionate presence more important than ever now — as our world weeps and our tender hearts ache with each fresh gasp.

Share your thoughts about resilience, grief, and the power of compassionate presence. I’d love to listen.

Elaine, I hope you realize how much you help others with Grief Matters. Not only those grieving (most of us are, in some way), but also those who have trouble fathoming grief because they haven't experienced it. Deeply appreciated!